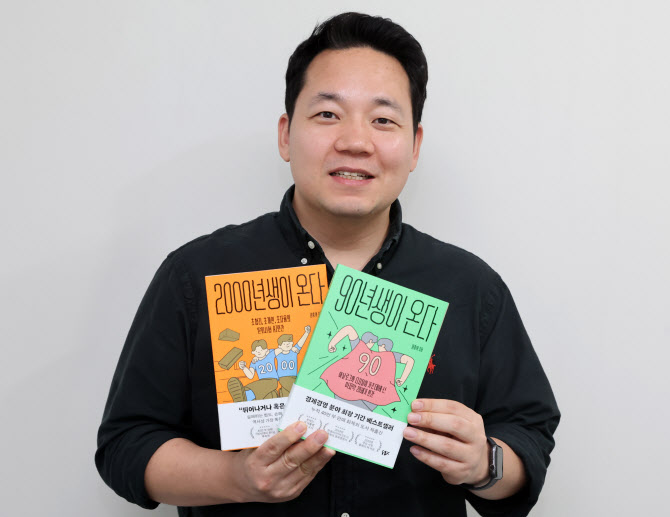

This is the statement from author Hong-taek Im(43), who wrote “90s Generation is Coming”(2018), a book that has sold over 400,000 copies as of last year.

In an interview ahead of the Edaily Strategy Forum, which takes place June 18?19, Im pointed to the deepening of generational conflict in Korea’s super-aged society. “It’s not that a particular generation is strange, but rather that times have changed,” he said. “Before criticizing young people as ‘selfish’ or ‘individualistic,’ we need to recognize how the era has shifted and look for ways to improve together.” He argues that the roots of social conflict lie not simply in age gaps, but in more fundamental differences in perception.

|

Anxious Millennials and Gen Z: “Survivalism” is the Reality

Korea is experiencing unprecedented level of low birthrates and rapid aging, making perspectives on the MZ(Millennial and Gen Z) generation complex. As the first generation of the low-birth era and one deeply familiar with digital environments, they are often seen as bold individuals who, armed with abundant information, know how to avoid financial losses. Yet they are also a group shaped by intense private and public education, sudden booms in cryptocurrency and real estate, and growing anxiety due to economic uncertainty and a tough job market.

According to author Im, the concepts of work, career, and money differ completely from those of older generations. He explained, “In the past, going to college meant you could predict a certain standard of living. Now, the upward curve has broken, and the future is unpredictable. The era where hard work guarantees success is over.“ He added, “Even working your whole life, it’s hard to buy a home, and there’s no guarantee you’ll get your national pension back. For the MZ generation, the traditional steps of marriage and childrearing no longer seem rational.”

Those born since the 1990s openly reject workplace customs like traditional after-hours company dinners, which older generations considered normal. When asked to join a dinner after work, they reply, “Why? Can’t we just have lunch together?” Some even ask for their share of the meal allowance if they don’t attend. Author Im shares this as a real-life example from his research. “We need to question whether lunch gatherings, which are technically break time under labor law, are appropriate. The key concerns for young professionals entering the workforce are fairness and avoiding unfair treatment.” he said, attributing many conflicts to differences in values.

He believes the same logic explains why young people are distancing themselves from marriage, childbirth, and parenting. He argues that behind the declining birth rate lies a perception among young people that having and raising children is not a rational choice. He stated, ”Rather than worrying about a distant population crisis, young people are facing immediate survival concerns.“ He emphasized that understanding generational perspectives should be a key part of addressing demographic changes.

|

Im also points out that these challenges cannot be solved by government alone. “Even pouring trillions of KRW into policy hasn’t significantly lifted the birthrate,” he said. For overcoming the demographic crisis, he argues, “The core of Korea’s population policy should start with employment, not birthrate policy. People need to experience work-life balance and feel financially secure before marriage and childbirth rates can increase.”

He describes Korea as an “intensely overwork society.” In 2023, Koreans worked an average of 1,872 hours annually - showing a gradual decline but still among the highest among the 34 OECD countries, behind only Mexico (2,207 hours), Chile (1,953 hours), and Israel (1,880 hours). As the June 3 presidential election approaches, the 4-day workweek has become a hot topic.

Im believes a full 4-day workweek is unrealistic for most companies, except for large corporations. “Reducing working hours is necessary, but the key issue is how to address wage cuts and economic polarization when implementing such a system,” he said. “In many workplaces, it’s still common for employees to be criticized for taking parental leave during their prime working years.”

He also criticized presidential candidates for neglecting youth issues. “I don’t see any real policies for young people. Political debate and policy for youth are lacking, while most attention is paid to senior voters,” he said. “Korea’s refusal to tolerate failure makes it one of the countries with the highest suicide risk. This is evidence that our society is deeply troubled. We need to analyze suicide as a key factor in the population crisis.”

These days, Im is focused on the concept of “adulthood.” “The notion of being an ‘adult’ has expanded in the era of 100-year lifespans, but age alone no longer commands respect anymore,” he said. “We need to know when to let go of previlege. Without reflection, a new era cannot begin.”

About Im Hong-taek:

△ Master’s in Information Management, KAIST Graduate School of Business, △ Former instructor for new employee orientation at CJ Talent Academy, △ Former brand manager, Food Division, CJ CheilJedang, △ Member, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Innovation Implementation Advisory Committee, △ Adjunct Professor, Myongji University Graduate School of Future Convergence Management (Present)

!["청년 ''도시 선호'' 수용해야…빈집 철거해 도시 밀도↑"[ESF 2025]](https://image.edaily.co.kr/images/Photo/files/NP/S/2025/06/PS25061901218t.jpg)

!["네가 거부하면 언니" 딸들 낙태시켜 가며 성폭행 [그해 오늘]](https://image.edaily.co.kr/images/vision/files/NP/S/2025/06/PS25062301295t.jpg)